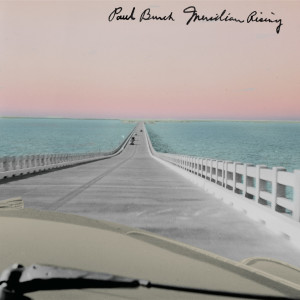

Photo by Emily Beaver

Click Here For Article and To Listen To “Meridian”

Revivalism in music often seems to be no more than a matter of style: a perfectly greased pompadour, a well-pressed rack of vintage dresses, some vintage equipment and the careful mimicry of a particular “hi-de-ho” or drawl. It’s the rare living musician who does the extra work to comprehend the past she or he pursues in its entirety, from the flashiest trends of the time to the notes in the margins. Paul Burch is that extra-hard worker who also happens to be gifted with an easeful way of getting his messages across.

The Nashville resident, who reached national prominence in the 1990s as a key player in the city’s Lower Broadway honky-tonk revival, makes music that’s often described as studious, but such terms don’t get at the fun he and his collaborators have within the parallel worlds they construct. For his latest project, Meridian Rising, Burch has gone all out, telling the life story of his hero Jimmie Rodgers in an imagined musical autobiography that’s as tunefully transporting as it is erudite.

Jimmie Rodgers was one of the first major musical celebrities of the twentieth century, and, in many peoples’ estimation, the father of country music. The Mississippi native lived a scant 35 years, but in that time he fully embodied the spirit of the age, melding rural white and African-American folkways within a city-wise style that was emotionally profound and danceable. He was a radio star, a man in the movies, a potent brand, a legend in his time. In Burch’s words, he was “the first American stylist of the modern age.”

Meridian Rising shares a lot with Loudon Wainwright’s Grammy-winning Charlie Poole Project and Guy Davis’s performance as Robert Johnson in the Broadway musical Trick the Devil. It goes into the bones of its subject while remaining joyful at the mere fact that this music and Rodgers’s story exists to be explored. With collaborators like Jon Langford of the Mekons and the Waco Brothers, Billy Bragg, Gary Tallent of the E Street Band, and fiddling Nashville treasure Fats Kaplin, Burch creates a rich environment through which his Jimmie Rodgers freely wanders, speaking in ways that jump the decades lost.

Burch recently answered some questions via email about Meridian Rising, whose title track you can hear for the first time. He’s also set up some nifty web pages about the project.

This is such a cool project — a deeper dive in many ways than a simple tribute album. What inspired you to take this approach?

I had been thinking about this for about 15 years, after I became enchanted with an unreleased version of “Let Me Be Your Sidetrack” which Jimmie recorded with Clifford Gibson, a blues guitar player from St. Louis. The more I listened to it, the more luminous it became. Clifford’s style reminded me a little of Robert Johnson — similar tunings and phrases. But more than that, I heard the duet as an example of Jimmie’s personality.

The song became a kind of portal, a Wizard of Oz moment, where I could enter his world as a musician, which is an aspect his biographers could only imagine. I thought writing from Jimmie’s point of view might be a wonderful challenge. I’m glad I waited a while. There were lots of crucial facts that came up just in the last few years.

How did you research the album? Did you consult with Barry Mazor [Nashville writer who wrote Meeting Jimmie Rodgers]? How is “researching” for a musical project different than researching for a writing project?

I did speak with Barry quite a bit, as well as Jimmie’s biographer Nolan Porterfield and Gary Giddins, who wrote a beautiful biography of Louis Armstrong. But the narrative that I was making was a bit more earthy. I cared about the facts but I was much freer in my approach. When I found a scene or fact that I liked, I would then daydream about it. For instance, Jimmie and his producer Ralph Peer had lunch with Stan Laurel and Oliver Hardy in Hollywood. When I read that, it put me in such a good mood! I thought perhaps they went to Musso and Frank, an old Hollywood hangout. That led me to looking at Musso and Frank’s menu and trying to imagine Jimmie and Laurel and Hardy in those posh leather seats, eating roast duck, maybe sneaking a bootleg cocktail. Now, that song didn’t make the album but that’s an example of how my mind works.

Was your goal to capture the sound of Jimmie Rodgers as well as his spirit? What did you ask of your collaborators, to get then in the right mind-frame for the album?

Yes it was. Before each song, I talked to the group about what was going on in the story. My thought was that every song would be scored to reflect the music that Jimmie would have heard at the time. Imagine being in New York City in 1928 with money in your pocket for the first time in your life. What’s playing at the movies? Who is in the clubs? Thinking that way allowed me the luxury of using a very wide palate of sounds. Near the end of the album, Jimmie writes a letter from New York to his wife back home in Mississippi in a song called “Sorry I Can’t Stay” — which indeed happened. The content of those letters has remained private. But I could imagine — knowing Jimmie’s letters that I have read — that he probably didn’t say outright, “I’m dying,” but he would have found a way to impart that he might not make it home. For that song, a National guitar was perfect. On “Ain’t That Water Lucky” I imagined Jimmie at an emotional precipice after he was diagnosed with tuberculosis and the death of his daughter; so I put him at the edge of the Mississippi River with instruments like oboe and piano, which could be a bit Gerswhin-esque but also get very gnarly. It was all a puzzle spread out on the floor. I wrote the titles first and then tried to write music that fit.

You have been called “a modern-day Jimmie Rodgers”; this album is a powerful way of both honoring that legacy and shaking off the label by showing much more specifically and deeply who Jimmie Rodgers actually was. But what does root your affinity for him? His sound? His biography? His attitude about mixing musical genres?

That quote was — and still is — a very lovely thought, and when it came, it did give me pause for thought as to just who Jimmie Rodgers was. I don’t mind being aligned as a “modern Jimmie Rodgers” as I think he was modern — all the way. You might say he was carelessly optimistic and free. You won’t find many artists that free. He was fearless to play what he liked. But then, every musician should be fearless to play something that moves them.

I recognize Jimmie’s love for asking musicians he admired to record. I do that quite a bit. When I hear music that moves me, I want to play it. If I’m charged by it, that’s all the motivation I need. I feel like I’ve got nothing to lose. I might not entertain everybody but I’d like to do something that everyone likes — my way of course! Jimmie created the idea of what it meant to be a people’s entertainer, which is why Leadbelly and Robert Johnson and Howlin’ Wolf performed his songs.

You were a key player in Nashville’s ’90s honky-tonk revival. Right now, the city seems to be going through about ten different transformations, some of them contradictory. Are you excited about what’s happening here, musically and otherwise? What does Nashville still offer a musician who wants to both explore and stretch tradition?

When I came to Nashville in 1994, the musicians I wanted to meet had been more or less thrown aside by the Nashville popular music community. Emmylou and Johnny Cash didn’t have record deals. Chet Atkins personally called the Opry and told them they should have me on and they all but hung up on him. And the R&B history was not even discussed. But today, my pal Jon Langford has his paintings up all over town celebrating Bob Dylan and Johnny Cash. So in that sense, there’s tremendous progress. The Country Music Hall of Fame should be given a lot of credit for challenging the city’s understanding of its own history. Where else could I shake the hand of Bobby Hebb? (Has there ever been a more uplifting song than “Sunny”?)

But yes, I’m disappointed at the loss of old buildings and history in Nashville and I think I share the sentiment of a lot of longtime residents that our dreams and nightmares are coming true. I would like to be able to buy fresh mozzarella and all, but not at the expense of a city block of buildings made by hand in 1890. There’s all this talk of “artisanal” but we’ve lost nearly every building actually built by people with true artisanal skills. Truthfully, this carelessness has been a long time coming ever since I-40 plowed through Jefferson Street and killed a vital—and thriving—African American business center in the city.

As for the music side, I’m always glad to hear that more good musicians are coming to town. “Tradition” is really all in the mind. The Earls of Leicester are introducing people to the sound of real bluegrass for the first time and it’s knocking them out. Let’s visit this question again in 10 years and see what’s left!

You love to explore the past on many levels in your music — in songwriting, in production approaches, and through instrumentation and vocal techniques — but it’s obvious that achieving a sense of immediacy matters a lot to you too. How do you make your historical explorations hop?

I have no idea how I make anything hop—but if it hops for you, that makes me happy. When I hear something that’s hopping, that’s where I want to go. If it’s new to me, I want to find the heart of what’s attracting me. Duke Ellington told an interviewer quoting “Summertime”:

Well, My Daddy was rich. My Mama was good lookin’. They made sure my feet never touched the ground. Then one day, someone said ‘Hey Duke, come over here…’ and so I did and then someone else said “Psst, hey Duke, come check this out…” and off I went. And now here I am.

As Sam Cooke said, that’s where it’s at!

Meridian Rising is out on Feb. 26.